After a break, I am returning to my series of short reviews on modern Southeast Asian fiction. This is a special two-parter, featuring two connected books that engage with the Vietnamese American refugee experience. There will be spoilers. As always I’m pleased to have had the chance to develop these thoughts as part of a course, so credit is due to my students—this semester there are two—as well.

Previous reviews:

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (1): Rachel Heng, The Great Reclamation

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (2): Gina Apostol, Insurrecto

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (3): Ayu Utami, Saman

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (4): Tash Aw, We, The Survivors

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (5): Thuận, Chinatown

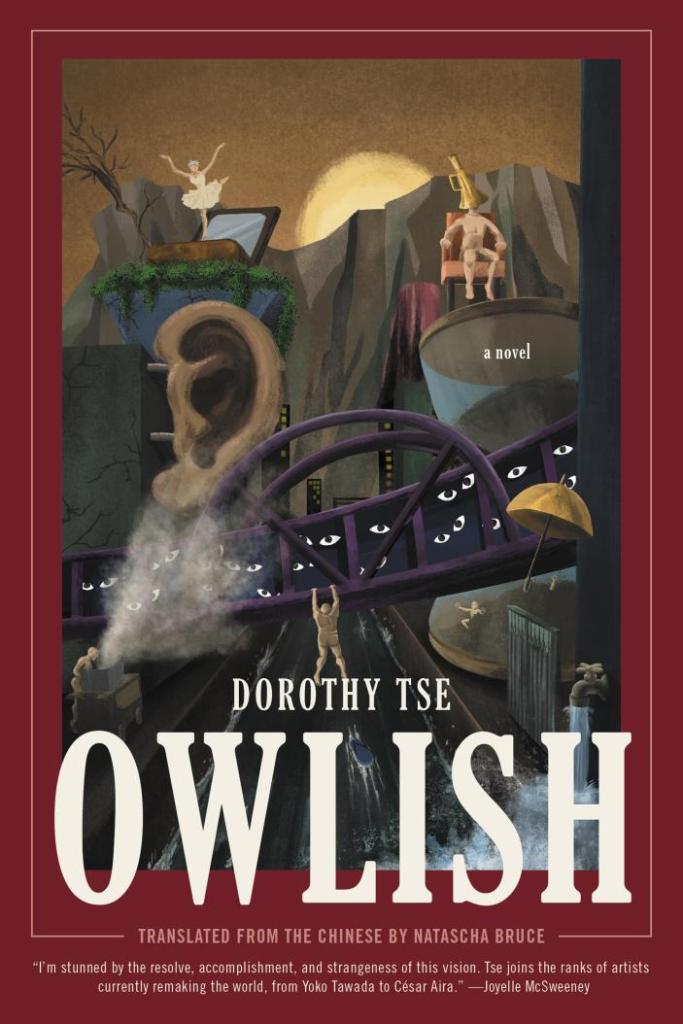

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (6): Dorothy Tse, Owlish

Although I will discuss both books here, I will start with the more recently published one first, as this is the order in which we read them.

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

If you have even a passing interest in Southeast Asian or Asian American fiction, you’ve probably heard of Ocean Vuong‘s monumental first book, which I first encountered through NPR. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is, at one level, the story of Little Dog, a Vietnamese American boy growing up in Hartford, CT, exploring his experience as an refugee, his relationship with his mother and his extended family, his race and sexual identities, and others.

Spoilers: we learn over the course of the book about Little Dog’s mother, a mixed race daughter of an unknown American soldier, and his grandmother, who left her South Vietnamese village after an unhappy marriage and made her way through the Second Indochina War as a sex worker.

At another level, this is a book about interweaving the American and the Vietnamese experiences in the late 20th century. That’s not even correct, though: the point is that the Vietnamese experience in America is the American experience. The book describes the racial landscape of Hartford, agricultural work in Connecticut*, with extended reflections on class and nation, and especially on white poverty, fentanyl and heroin, violence, and trauma across generations. And moreover, on the intimate connections that are not there: fathers who are not biological fathers, grandfathers who are not biological grandfathers, and fathers who are biological fathers but do not parent, and so forth.

I will resist injecting too much of my own personal reflections into this discussion, but the book’s setting in Hartford is important. Southern New England happens to be my own entry point in the geography of Southeast Asian American life: humid summers and damp cold winters, a racial and ethnic landscape that does not match what one learns about in high school U.S. History classes. There are other Southeast Asian Americas, in California and Washington State, Philadelphia and Minneapolis, Houston and North Carolina and Hawai’i, and everywhere else as well.** I don’t know all the connections among these Southeast Asian Americas, just that the diaspora is aware of itself as a diaspora within a sprawling continental empire.

Stepping back from the subject matter, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is also an important piece of literary fiction, in which the writing itself is as much the centerpiece as is the content. Vuong is a poet, with an amazing way with words, describing grinding rural white poverty and the economy of the nail salon. His writing about sex and violence is artful and clinical at the same time. The book is nonlinear, multiperspectival, poetic. You must read it closely and carefully to see all of the layers.

lê thị diễm thúy, The Gangster We Are All Looking For

In an interview with Literary Hub, Ocean Vuong described lê thị diễm thúy‘s The Gangster We Are All Looking For as a formative influence. He focuses on the narrative structure:

thúy not only breaks the rules of traditional Western narrative; she insists that such rules can be consciously rejected because their rubrics were made without considering the bodies her book holds—even at this risk of rendering it, in the eyes of critics trained to recognize and celebrate hegemonic styles, as nonsensical or wrong. The result is a bold and empowering refusal of conformity in search of other ways of speaking and being.

In my own read, though, I hardly noticed any of these aspects of lê’s book. What took me in, instead, was the story itself. thúy’s account is autobiographical, the story of growing up in a boring suburb somewhere in San Diego County, the daughter of two hard-working, troubled parents who had lost two young children while fleeing Vietnam after 1975. A heartbreaking spoiler is that thúy’s birth name was not thúy: that is the name of an older sister who drowned in a refugee camp in Malaysia. Owing to a mixup during processing, thúy ended up with her older sister’s name and it has stuck ever since.

The Gangster We Are All Looking For is thúy’s father, a Buddhist and a criminal from northern Vietnam who married a Catholic from the south during the war. He endured the tragedy of learning of his son’s drowning while interned at a reeducation camp before fleeing to the United States with thúy (her mother came separately). In the U.S. he works several jobs alongside his relatives, thúy’s “uncles,” before ending as a gardener. He drinks too much on the weekends, and when reunited with his wife in the U.S., they build a life anew. They fight, they cry, they lose their home. Their daughter is haunted by her lost brother and sister, and flees east for college. But before she does, she relates the experience of growing up in hot sunny southern California, the smells of mimosa and night jasmine, the boredom of the suburbs when you have no car, the experience of being lumped with the Cambodian and Lao and Hmong of the area as just another “Yang.”

There are parallels between Vuong’s narrative and lê’s. Besides the obvious diasporic linkages, their rooting of American refugee experience in the tragedies of the war in Vietnam, there are issues of race (thúy’s father has a high nose, a sign of his partial French ancestry), of sex (thúy’s experiences in a “kissing box” are presented much more tenderly than Little Dog’s first sexual forays). There is also a parallelism in that the narrators know their families’ checkered pasts. Refugee histories are real and present, and there is no time for mythmaking. The ancestors are not all nobles.

Read together, these books were a moving reflection on not just the refugee experience, or the Vietnamese American experience, but on America itself. It led me to remember my own upbringing; my hometown had its own Vietnamese refugee population, after all. It brought back heavy memories of my own experiences with refugee communities in southern New England. These are not just a stop along my own intellectual journey, they make me who I am today.

I do not think of these two books as Asian American fiction (although they are), or refugee fiction (although they are), but rather as American fiction. The point of these books, as I see it, is that Vietnam is here, just as America was there, and we constitute one another. Just like Fievel sings about sleeping underneath the same big sky, lê’s parents look to the ocean in California to see the same water that claimed their children, the water that they crossed to find America.*** That ought to be everyone’s story.

NOTES

* Before reading this book, I had no idea that there was something called Connecticut Shade Tobacco. Amazingly—although perhaps not surprisingly for the Nutmeg State—the tobacco cultivar used in Connecticut is a Sumatran variety. A New World crop like tobacco moving to Sumatra and then coming back to Connecticut is such a wonderful expression of the Columbian Exchange.

** My Vietnamese class in grad school had students from Rancho Palos Verdes, Terra Haute, Bridgeport, Cincinnati, Albany (the one in NoCal), Philadelphia, Dallas, and other places I’ve forgotten, all but two of us the children of South Vietnamese refugees. RIP Anh Brandon.

*** The Vietnamese word for the United States is Mỹ. This is notable because mỹ is also the Vietnamese word for “beautiful.” It is also lê’s mother’s name, and through the fence of the internment camp, she calls out to her husband from the north (named Minh, wink wink), Anh Minh, em Mỹ. Which you might translate as “oh brother, it’s your sister.” But there are other readings too.