In an earlier post about Indonesia's 2019 elections, I examined the correlates of support for presidential candidate Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and VP candidate Ma'ruf Amin. The central message in that analysis was that non-Muslims and Javanese Muslims voted heavily for Jokowi, whereas non-Javanese Muslims were the main supporters of the opposing ticket of Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno.

But this was not the only election that took place that day: Indonesians also voted for members of the People's Representative Council (DPR), Indonesia's legislature. Unlike Indonesia's presidential election, run on a first-past-the-post model, Indonesia's legislative districts are multimember districts. This gives more room for differentiation among the more than a dozen parties that contested these elections. Given the role of Islam in explaining presidential results, it is natural to ask whether this also explains the legislative voting patterns as well.

To investigate this question, I use the same data sources as before to calculate support for Islamist parties—adding together PPP, PKS, and PBB)—as a fraction of all legislative votes cast in each administrative district. The figures below plot this against the Muslim population share for each district, and compare those results to vote shares going to the explicitly non-Islamist parties Golkar and PDI-P.

These results show, unsurprisingly, that Islamist parties are more popular in Muslim-majority districts than in non-Muslim-majority districts. But note that the vote share for Islamist parties is never particularly high. Also unsurprisingly, PDI-P, the Indonesian party that most closely approximates a secular nationalist party, does best in non-Muslim districts and tends to fare worse in Muslim-majority districts on average.

If we break out the Islamists into individual parties, we see a similar result.

Once again, these parties don't do particularly well (check out the y scale), but they do do better, as we might expect, in heavily Muslim regions.

All of these results are based on district-level data. It would be even more revealing if we could take the results down to a lower level of aggregation, but unfortunately I do not yet have compiled demographic data at a lower level of analysis. But thanks to Nick and Seth (who provided the data for the first analysis) we do have vote returns at the level of the village (or, in urban areas, something like the ward). And we although we do not have demographic data, we can look at both presidential and legislative results together to provide a bit more insight on the role of Islam in the 2019 elections.

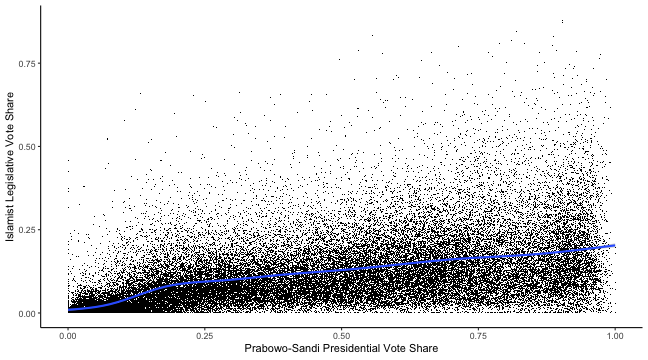

One thing we can do is look at the aggregate vote share for Islamist parties at the village/ward level, and compare that to the presidential results. If Prabowo-Sandi earned more votes in villages where Islamist parties did well, then this is evidence—albeit indirect and circumstantial—that the effects of Islam on vote choice are more than just demographic in nature.

And, in fact, this is what we find. Each tiny dot in the figure below is a village or a ward. And when we plot all 50,000+ of them, Prabowo-Sandi vote share versus Islamist party vote share, there is clearly a positive (if modest) correlation.

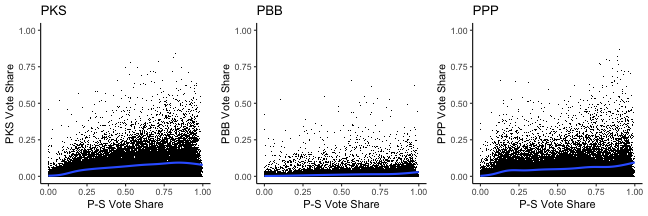

Now, officially speaking, the Islamist politics here ought to be more complicated. After all, PPP joined Jokowi's coalition rather than Prabowo's. But contemporary Indonesia's partisan alignments are famously fluid, and it would not be surprising if voters who supported Islamists in the legislature also supported Prabowo-Sandi. We can check this by once again breaking down the results by Islamist party.

That there is a positive relationship between PPP legislative vote share and Prabowo-Sandi results tells you just how strong these partisan coalitions are. For those curious, it's also possible to show these results in a regression format (controlling for turnout and 5000+ kecamatan fixed effects which wipe out most interesting differences across Indonesia's regions).

## ## ============================================================================================================ ## Dependent variable: ## --------------------------------------------------------------------------- ## islamist_share ppp_share pks_share pbb_share ## (1) (2) (3) (4) ## ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ## ps_share 0.158*** 0.052*** 0.097*** 0.009*** ## (0.006) (0.004) (0.004) (0.001) ## ## leg_total 0.00000*** -0.00000** 0.00000*** -0.00000* ## (0.00000) (0.00000) (0.00000) (0.00000) ## ## ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ## Observations 54,278 54,278 54,278 54,278 ## R2 0.692 0.598 0.645 0.560 ## Adjusted R2 0.660 0.556 0.608 0.514 ## Residual Std. Error (df = 49135) 0.061 0.042 0.044 0.017 ## ============================================================================================================ ## Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 ## OLS with kecamatan fixed effects, standard errors clustered by kecamatan

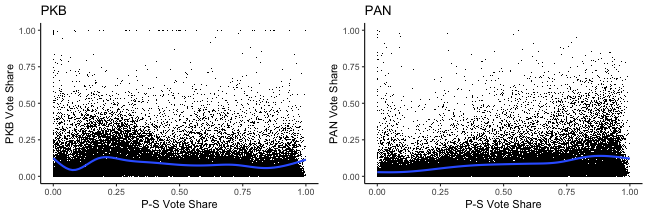

The last link in this story are two parties that occupy an interesting position in Indonesian politics. PKB and PAN are both historically linked to important Muslim mass organizations (Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, respectively), but neither of them is Islamist. PKB joined Jokowi's electoral coalition—NU's leader Ma'ruf Amin served as Jokowi's running mate—but PAN joined Prabowo's coalition. How did that translate into partisan coattails at the legislative level?

PAN did better in places where Prabowo-Sandi performed better. But the same is not true for PKB. Its performance is uncorrelated with Prabowo-Sandi's performance. This is even true in a statistical test:

## ## =========================================================================================================== ## Dependent variable: ## -------------------------------------------------------------------------- ## islamist_share pan_share pkb_share ## (1) (2) (3) ## ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ## ps_share 0.158*** 0.114*** 0.001 ## (0.006) (0.006) (0.005) ## ## leg_total 0.00000*** 0.00000 -0.00000** ## (0.00000) (0.00000) (0.00000) ## ## ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ## Observations 54,278 54,278 54,278 ## R2 0.692 0.657 0.728 ## Adjusted R2 0.660 0.621 0.700 ## Residual Std. Error (df = 49135) 0.061 0.063 0.061 ## =========================================================================================================== ## Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 ## OLS with kecamatan fixed effects, standard errors clustered by kecamatan

With huge amounts of statistical power to detect a really small effect, we can confidently conclude that the coefficient on P-S in the third column is a precise zero.

It's hard to know what exactly to conclude about ideology, identity, and partisan voting from this last set of results. But village-level demographic data will help to sort these findings out. Watch this space for more.