As part of a long term, multi-paper project on decentralization and governance in Indonesia (see e.g. here and here), I am putting together some data on the social structure of colonial Java. I am most interested in colonial migration and ethnicity. Put coarsely, the Dutch colonial regime recognized three kinds of people in Java: natives or indigenous people (Inlanders), Europeans and other “assimilated” persons (Europeanen en gelijkgestelden), and a residual category of “foreign Easterners” (vreemde Oosterlingen). This last category had two main categories: Chinese and Others, the majority of whom (at least in Java) were Arabs from the Hadramawt. (The rest were Indians, Malays from British Malaya, Thais, and some others. Japanese, interestingly enough, were counted in the “other assimilated persons” category alongside the Europeans.)

It is obvious to anyone who visits Indonesia today that the Chinese Indonesians play an important economic role across the island. It is less easy to see it, but Arab Indonesians do too. This economic differentiation between foreign Easterners and the native or indigenous peoples of Java dates to the Dutch colonial period, if not before.

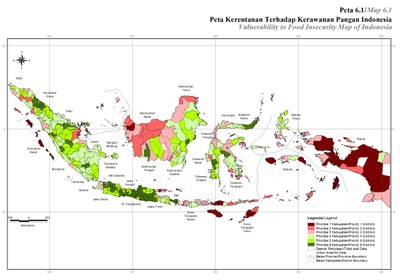

But not every part of Java was equally penetrated by Chinese and other foreign Easterners. As a way to visualize this, Cornell Government PhD student Diego Fossati has produced two fascinating maps of colonial settlement in Java that illustrate the spatial distribution of Chinese and other foreign Easterners across the island. The data were extracted from the 1930 Census of the Netherlands Indies, or Volkstelling 1930, and I have used maps of Dutch administrative boundaries (at the Regentschaap level when possible, or at the District level when necessary) to assign data on settlement by Chinese and other foreign Easterners in 1930 to contemporary administrative units (kabupaten and kota). I omit Jakarta from this exercise because the borders within Batavia are too difficult to match.

First the Chinese:

Now, for the “other foreign Easterners,” recalling that most of these—but not all—were Arabs:

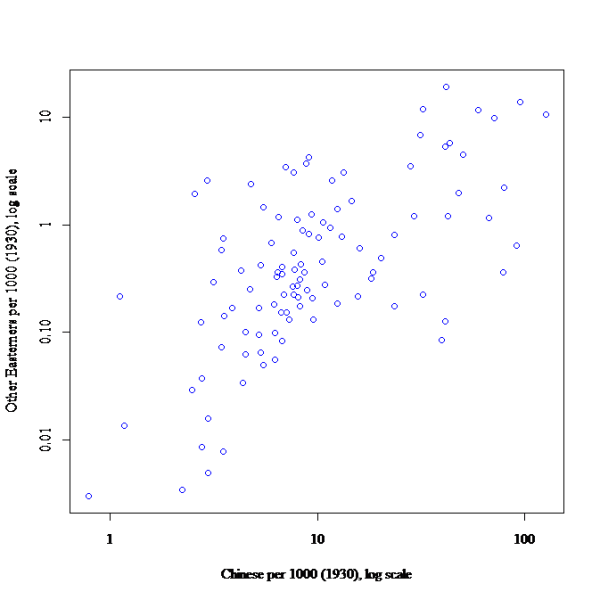

As fascinating as the maps are, it is hard to see from them how Chinese and other foreign Easterner settlement covary, so I have also produced a scatterplot of the two.

Such maps and figures are great illustrations of historical data. But some readers have probably guessed that I have a lot more in mind with this than making pretty maps of colonial demographics. I think that this variation in colonial social structure is consequential: it actually explains something important about local politics in Java today. More on that to come, hopefully soon.