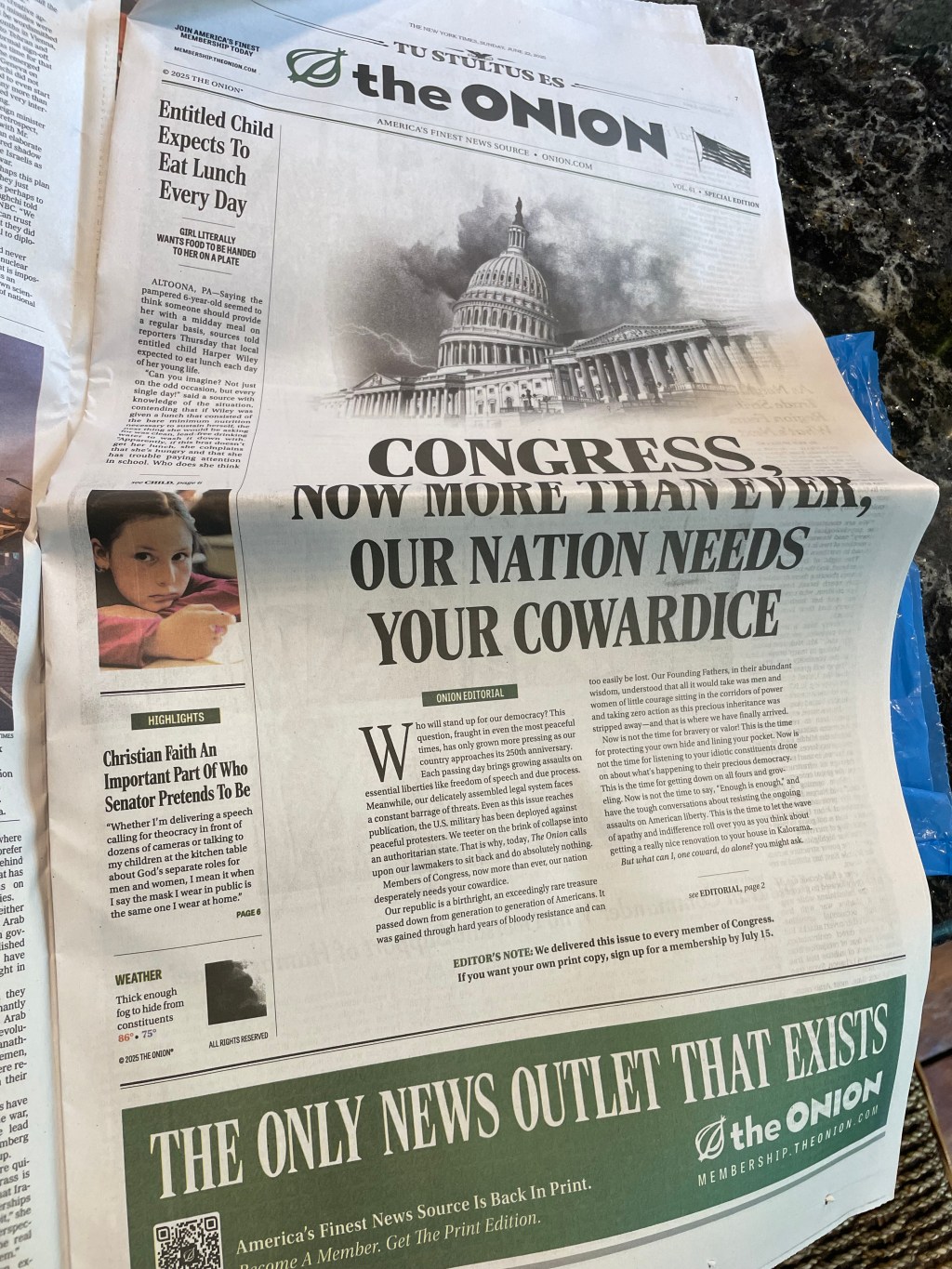

At a time when the U.S. government has floated the idea of a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, and tech oligarchs question the viability of the sovereign state in the age of blockchains, there is a need for some clear and analytical thinking on the political economy implications of cryptocurrency.

An old college buddy of mine has contributed some much-needed clarity by studying the possibility of regulation under decentralized finance. In a world where trusted intermediaries are no longer necessary due to the availability of smart contracts, can a decentralized and permissionless system provably guarantee that some transactions are forbidden? The answer is no. He and his coauthors write,

As these new developments use computational systems, they must be bound by existing results from computation theory.

The implication of their argument is that financial regulators cannot rely on a DeFi architecture if they also want to do things like implement exchange controls or ban money laundering.

The same constraints bind when we consider the political economy of cryptocurrencies. We can adapt the quote above accordingly: as crypto engages with political and economic systems, it is bound by existing findings from political economy.

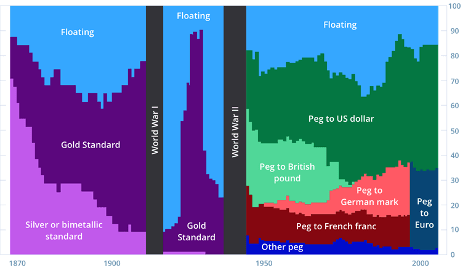

Inspired by these ideas, Mark Copelovitch and I have recently completed a working paper that contributes some analytical clarity to current debates about blockchains, cryptocurrency, and state sovereignty in an international system in which states issue fiat currency. The basic premise of our argument is that crypto is, aspirationally, money—a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account. Thinking about crypto this way clarifies which kinds of actors value crypto and for what purpose, the role of ideas in supporting crypto, and the stakes of crypto as a complement (or substitute) for fiat currency at the national and international system levels.

Our working title is “The Political Economy of Shitcoins.” And here is the abstract:

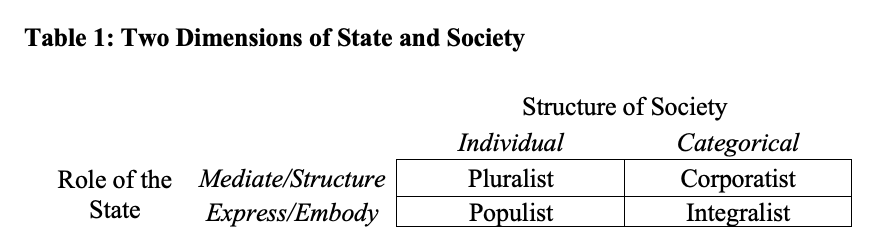

We study the political economy of cryptocurrency in a global economy comprised of states that issue fiat currency, considering the implications of crypto from the position of users, issuers, states, and the international system. The political implications of cryptocurrency follow from its ability to perform the three function of money: unit of account, medium of exchange, and store of value. From these foundations, we draw on the established literature on the political economy of international monetary relations and international finance to derive predictions about the future of cryptocurrency in a world of sovereign states. We describe four possible futures for the international monetary system: a world without cryptocurrency, a world in which cryptocurrency exists alongside fiat currency, a world in which cryptocurrency has replaced traditional fiat currency, and a techno-futuristic world in which cryptocurrency spells the end of the Westphalian state system. We evaluate the political and economic stability of each of these four scenarios. We conclude that the most like scenario is one in which crypto survives alongside traditional fiat currency, but also highlight that the future of cryptocurrency is a battle over the future of sovereign authority itself.

Lest you think that this is a niche topic, the author of The Network State is a former Andreesen Horowitz partner who has a Substack where he recently posted that All Property Becomes Cryptography. He has also set up shop for his Network School in the failed megaproject of Forest City, Malaysia. This is relevant to my interests on so many levels.