This is the third in a series of short reviews on modern Southeast Asian fiction. There will be spoilers. As always I’m pleased to have had the chance to develop these thoughts as part of a course, so credit is due to my student as well.

Previous review:

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (1): Rachel Heng, The Great Reclamation

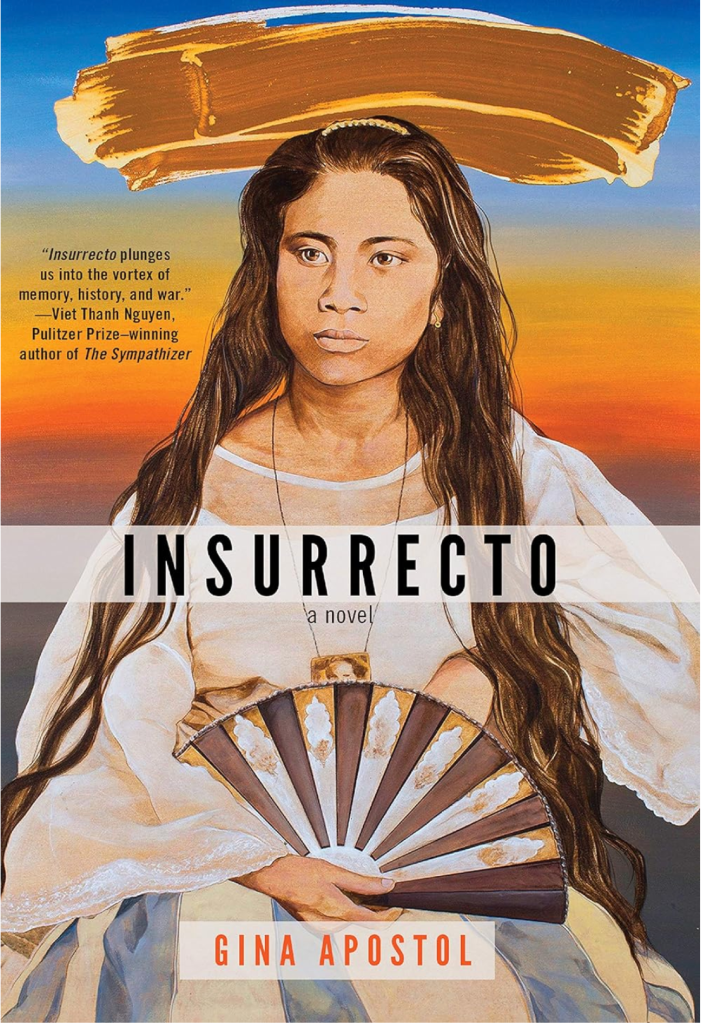

- Short Reviews of Modern SEA Fiction (2): Gina Apostol, Insurrecto

Ayu Utami, Saman

Back in graduate school, I wrote a dissertation about the political economy of regime change in Indonesia and Malaysia. I was in college when the Soeharto regime fell and when Mahathir fought Anwar and the IMF; by the time I had decided that maritime Southeast Asia would be my subject of research, Soeharto was long gone and Mahathir had retired (which was a thing that Mahathir once did). This meant that I learned about the turbulent events of 1997-98 indirectly, by reading about them and asking people about them.

The mid-2000s, when I was doing the field research that informed my argument, was an interesting time. The crisis was still very memorable—there were still burnt shopfronts in Glodok, and people would still scream at you in the KL exurbs about currency speculation—but things had changed in both countries. One thing that was most notable in 2004 was how much Indonesia’s political opening had led to an explosion of critical discussion of just about anything in the public space. Not just politics, not just history, but things like sex, gender, religion, the media, capitalism, and re(op)pression. Topics that had never been open for public discussion since at least the 1960s, if ever. It was a very open time.*

That is why I am sorry that I never read Ayu Utami‘s Saman before now. It is a kaleidoscopic novel, discussing female sexuality in raw, provocative, and sometimes amusing ways.

Four of the central characters are women in their 20s and early 30s, and we meet them in the context of direct conversations about desire, intimacy, and sex itself. One story line follows Laila, a 30 year old virgin, as she pines after a married man named Sihar, whom she plans to meet him for a tryst in New York City. Another follows Yasmin, who encounters the titular character, a man named Saman, after a chance encounter with Sihar and Laila (Yasmin and Saman later do meet in NYC; more about Saman later). Still another story line follows the female character Shakuntala, who is ravenous and unapologetic about her sexual appetite and experiences. There is an air of magical realism in the prose; when Shakuntala describes her youthful sexual encounters with “ogres” and her mother’s warning that she is “made of porcelain,” it seems obvious that this is a metaphor, but the prose is just magical enough to make you wonder.

Like many younger Westerners in Jakarta in the mid-2000s, I was adjacent to (but not affiliated with, or participating in) the modern art, literature, and music scene. Most commentaries about Saman describe how it influenced the sastra wangi [= “fragrant” literature] movement. I remember this, and I remember events at TIM and so forth. Reading Saman brought me back to discussion groups, coffee- and kretek-fueled conversations about Julia Suryakusuma‘s Sex, Power, and Nation, and the air of possibility and critique, especially among the ritzier segments of Jakarta, Bandung, and Yogyakarta. The book is dedicated to Komunitas Utan Kayu, which intersected with Jaringan Islam Liberal [= Liberal Islam Network]. I was close with some of the key players among the latter, and they shaped my thinking about a lot of things.

But I wasn’t in Indonesia for the release of Saman, which happened to coincide with the crisis of 1997-98. I don’t know Saman was released before or after Soeharto’s fall, but one does note that the exchange rates quoted in the book definitely imply that the book was written before the crash. I suspect that the acclaim that Saman received within Indonesia, becoming a true bestseller, was only possible because it coincided with a period of rapid political change, and an opening of civil society and intellectual space.

Reading this book a quarter century after it was written, and with my own background in Indonesia as just described, I do notice how powerful the descriptions of sex and sexuality are. These women are not Suryakusuma’s State Ibus. But I equally notice that the title character is Saman, not the four women who dominate the English-language coverage of the book. And I note the themes of capitalist domination and ecological destruction as much as I do themes of sex and intimacy.

Saman’s character is by far the most fully developed character in the book.** As we learn, he was born Athanasius Wisanggeni to a well-off Javanese Catholic family, and took holy orders to become Romo Wis [= father Wis]. He grew up outside of Prabumulih, in South Sumatra, and after schooling in Java returned home to become the priest in a local community.*** Once there he comes to confront the power of the extractive sector to control the local economy and society, and suffers accordingly. In the end, he leaves the faith. When we first meet him, it is many years later, and he has taken the name Saman.**** He is now an activist, and we meet him because Sihar (remember him?) contacts him after Sihar and Laila, who works as a reporter, witness a crime on a natural gas drilling platform off the Anambas Islands.

These kinds of intersections among various story lines are what make Saman such an interesting read. In reading together with the student, we came to the view that Saman represents a vision of the ideal man: he is pure, he is pious, he is noble in thought and in deed, unlike all of the other women in the book. It led us to think about assumptions about gender and sexuality in Southeast Asia: in Western academia, there is a view the traditionally, women were relatively more powerful and autonomous in Southeast Asia than they are in other parts of the world. In fact, this led us to pick off my shelf an old book that I bought for my first undergraduate class in the anthropology of Southeast Asia, Aihwa Ong and Michael Peletz‘s Bewitching Women, Pious Men, which is where I first encountered this view. From page 1 of the volume:

Dominant scholarly conceptions of gender in Southeast Asia focus on egalitarianism, complementarity, and the relative autonomy of women in relation to men—and are framed largely in local terms.

My student quipped: “This should be the title of the book! Not Saman.” Good one!

I’m conscious as well of just how cosmopolitan everyone in this book is. Much of the dramatic action takes place in New York City, which was all but unimaginable in the 1990s for anyone but Indonesia’s globe-trotting elites. And many passages in the book take the form of email exchanges, taking place—on the book’s own timeline—in 1994. I paused to think about this, because I did not receive send or receive an email until the summer of 1996, and the idea that two people could carry on trans-Pacific a romantic dialogue via email in 1994 is pretty interesting.***** I note that one minor background figure in the book, someone named Sidney with a New York apartment, is definitely someone I know.

In all, these thoughts help me to place this thoroughly enjoyable book in its historical context. And, also, to think about the random series of fortuitous connections that link me indirectly to the times and places here.

Notes

* This is one reason why I firmly believe that democracy really does matter. Just the possibility of freedom of conscience in public spaces is irreplaceable, and this is truly impossible without the minimal protections on individual expression afforded by a minimal democracy.

** In my understanding of literary criticism, which dates from my high school English classes, Saman is a round character, and the others are flat.

*** I took particular note in this part of the book that Utami describes how Prabumulih had changed in the intervening years:

The name of the street had changed, from Kerinci to Sudirman, from the name of a mountain in Sumatra to that of a Javanese general.

Seems like an important detail.

**** Saman doesn’t mean anything in Indonesian. There is a part of the book where a character speculates about Saman’s name as having been chosen because it sounds leftist (e.g. like Stalin, Lenin, Trotsky, Aidit). I think it sounds like semen and that that’s the point.

***** It reminded me of Jim Siegel‘s essay on the student protests of May 1998; specifically, a comment about a young women who remarked that her Softlens prevented the tear gas from affecting her.