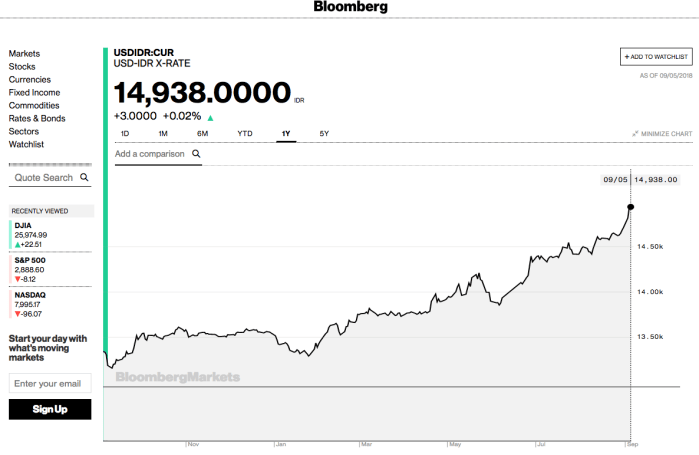

The Indonesian rupiah finds itself beset by international currency troubles. The word that jumps out to me in the Indonesian press coverage and on Twitter is anjlok, which means to plummet or to fall rapidly (see e.g. here). The last time that I saw the word anjlok used to describe the rupiah’s value this often was in old press clippings from the late 1990s, describing the Asian Financial Crisis, when the rupiah plunged from Rp2000/USD to Rp14000/USD in just a few months.

By contrast, the current troubles don’t seem so bad.

The worry is about the latest jump in the IDR/USD exchange rate over the past two weeks, which is worrying for certain but not nearly comparable to the financial (and subsequently macroeconomic and political) catastrophe that accompanied the rupiah’s collapse in 1998.

But it was in this context that an alert graduate student forwarded me this tweet:

#Indonesian President Joko Widodo said that external factors were behind the #rupiah's fall to 20-year lows. What nonsense. If the US & IMF hadn’t plotted to overthrow Suharto 20 yrs ago, Indonesia would have a currency board & a sound rupiah. https://t.co/d0XXEEYujS

— Prof. Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) September 5, 2018

There is so much going on here.

Take first the tweet’s author, Steve Hanke. Hanke has made a name for himself in the past thirty years as an ardent defender/proponent of the currency board system, a kind of exchange rate management institution in which a government body pledges to exchange local currency for benchmark foreign currency and keeps reserves on hand to accomplish this. Hanke is bullish on currency boards! Here he is tweeting on Turkey:

Turkey’s Finance Minister Albayrak says cutting inflation is a priority. If he means business, he should implement a gold-backed currency board. Currency boards kill inflation. They have been implemented in 70 countries and never failed.https://t.co/CSiIL2WW6C

— Prof. Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) September 5, 2018

The mind boggles at this sort of claim. It strikes me as much more credible to argue that currency boards rarely fail, or that when they fail it’s not so bad, but then again we live in the era of the Big Lie.

The problem with any fixed exchange rate system is that without capital controls, domestic governments sacrifice macroeconomic policy autonomy (the old Mundell-Fleming Trilemma). There is nothing magical about calling the fixed exchange rate promise a “currency board” rather than “the moon and sixpence” or something else. And because currency boards are political institutions created by politicians, they are obviously inherit any credibility problem that a government might have when it faces a run on its currency. Of course, the idea behind the currency board is that the strict pledge not to interfere in the currency would itself become the source of greater credibility. But that pledge is also a political act, and requires a strong signaling and credibility logic to sustain (“only a government that’s really serious would pledge something like this, so we infer that it must be credible”).

For Indonesia watchers, seeing Steve Hanke tweet about currency boards and Indonesia is quite the blast from the past. But there’s more! That tweet also conveys Hanke’s views about the fall of Soeharto as being not just the result of the crisis, but rather of plot by the US and the IMF to overthrow him. Why does he hold such beliefs? Because back in February 1998, Hanke was a key player in trying to convince Soeharto to implement a currency board system at the height of the crisis.

I wrote about this a month and a half ago, in a discussion of recently declassified material from the last years of Soeharto’s New Order. Here’s President Clinton’s quote again:

If the rupiah falls, you will lose your reserves. And if the currency board is caught short and falls, you will lose the reserves as well, just quicker.

You can see how this sort of claim would annoy any proponent of a currency board system. In the end Soeharto didn’t go for the currency board proposal—and very clearly, both the US and the IMF were sharply critical of this proposal—but couldn’t hold onto power in the midst of dramatic economic collapse. Hanke thinks that this is evidence that the currency board would have saved Soeharto, and the rupiah too.

If you’re wondering if Hanke maybe has a point (and he is not alone in his interpretations, see e.g. Ross McLeod here [PDF]), you might have a snicker at this February 16, 1998 article in Barron’s talking about successful examples that Indonesia might hope to emulate.

Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan noted the currency boards in Hong Kong and Argentina have worked because “the political will and policies required” have been present.

Hard to see how Soeharto possessed “the political will and policies required” to sustain a currency board. But this exchange rate policy footnote remains interesting when viewed with twenty years’ hindsight.