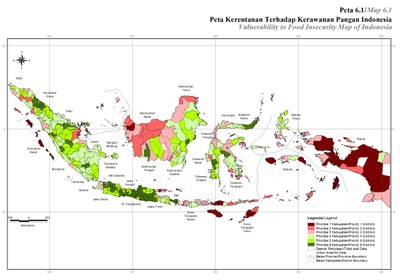

Yesterday Cornell SEAP series welcomed a visiting scholar from the State University of Papua who presented on food insecurity in Papua on our weekly Brown Bag. The talk was grimly fascinating. Papua and West Papua, the two provinces at the eastern end of Indonesia which occupy Indonesia’s portion of New Guinea, has always been a (literal) outlier for Indonesian studies. The presentation showed clearly that amid abundant natural resources, relatively strong economic growth, nearly every district in these two provinces suffers from dangerously high rates of food insecurity.

This is not starvation (although this does happen), but something more like systemic malnutrition or high variance in food availability. There was one image of four Papuan boys suffering from stunting which will stay with me for a long time.

Since at least Bates 1981, we have known that famines and food insecurity have political rather than environmental or agricultural causes. Just so in Papua. I asked the presenter about how political decentralization in Indonesia has affected the ability of local governments in Papua and West Papua to adopt good developmental policies. I will not post her response here, but suffice it to say that it was not a positive one. Moreover, there was a sense in her remarks that district-level governments in Indonesia (the district being the tier of government most empowered by decentralization, as opposed to the village or province) really aren’t where the main problems lie. Local governments aren’t the one’s responsible for plans to clear huge swaths of land in Papua in order to plant rice for export to the rest of Indonesia, or non-food crops for the rest of the world. After all, Papuans traditionally do not eat rice (although this is changing) and rice does not really grow well there anyway (which is why Papuans traditionally do not eat it).

All of this dovetails very well with a paper that I recently finished on accountability and Indonesian development in contemporary era. I’ll be presenting it in a workshop on oligarchy and accountability at the University of Sydney this December. I conclude the paper by writing that “We simply do not know enough about the relationship between local policymaking and national politics even to describe the interaction between institutional innovations, the national oligarchy, and informal political power in the regions.” Yesterday’s presentation on food insecurity in Papua tells me one thing: that’s where I ought to go to look.