President Trump has now been impeached, and the floor debate prior to the vote tells us something about the depths of America’s emerging regime cleavage. As I wrote in Politico several weeks back, this term refers to

division within the population marked by conflict about the foundations of the governing system itself—in the American case, our constitutional democracy. In societies facing a regime cleavage, a growing number of citizens and officials believe that norms, institutions and laws may be ignored, subverted or replaced.

Congressional floor debate in such circumstances, as every Congress specialist tweeted yesterday, are not actually a debates on the merits of the issue at hand. They are opportunities for Members of Congress to speak to their constituents. And what we heard in those debates, for those of you who had the stomach to listen to them (I did not), revealed that the GOP is now converging on a unified message that to even question the President’s actions is to threaten American democracy.

Greg Sargeant wrote a nice column yesterday that illustrates how the impeachment proceedings have pushed the GOP towards and ever more cynical position on the illegitimacy of any Constitutional opposition to the president. Focusing on Kevin McCarthy statements about the House Democrats “defying the vote of your own constituents,” he suggested that for the GOP,

the only voters that matter are the ones who voted for Trump in 2016 — those who elected the Democratic House don’t exist — and as such, Trump cannot be legitimately impeached simply by virtue of having been elected.

This idiotic argument undermines itself — impeachment can only be directed at a president who was previously elected by definition — but it’s the actual position held by Trump and Republicans, who regularly call impeachment a “coup.”

Trump cannot be legitimately impeached, and he is absolutely within his right to use the levers of government to corrupt the next election, to try and evade accountability at the hands of voters. And there is no legitimate mechanism to constrain him from continuing to do just that.

I, like many who have been horrified by the debasement of the GOP and its utter dominance by President Trump, have long been cynical about the willingness of the GOP to rein in this administration’s corruption and abuse of power.

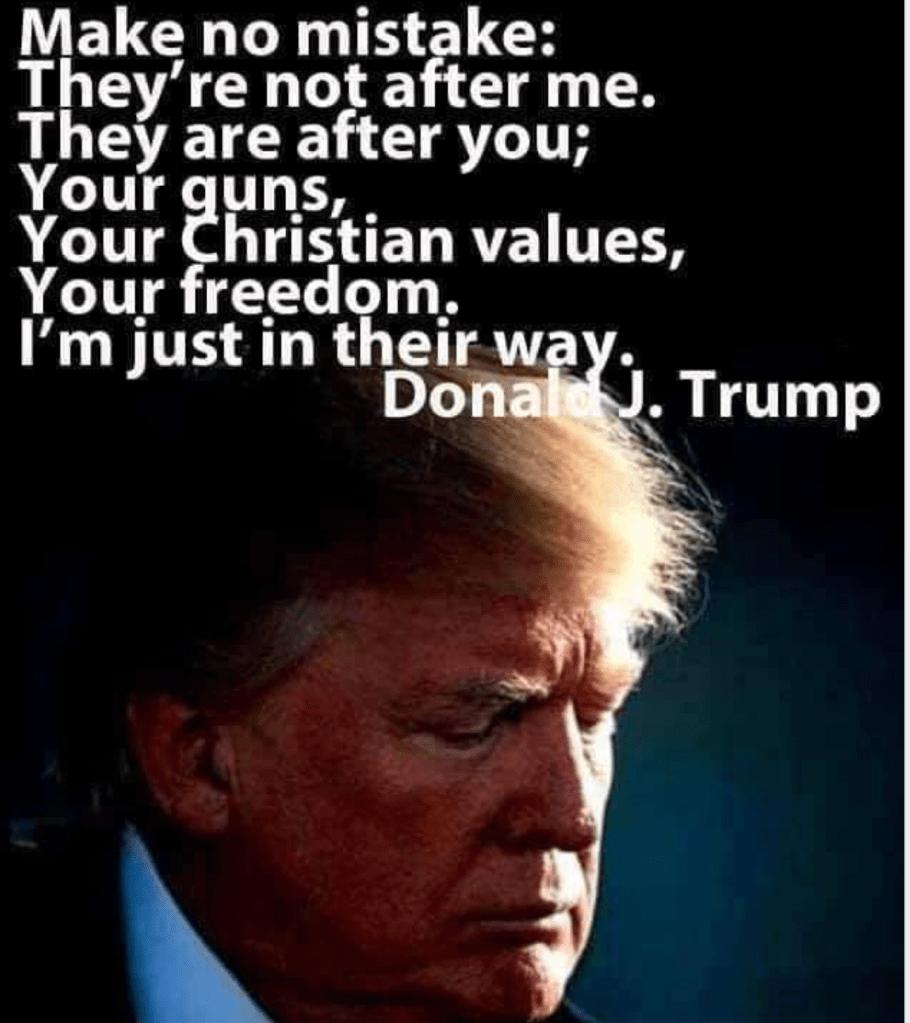

But what we are witnessing is something worse, now: the message is that to remove the president is to attack democracy. Or, as evocatively put in a meme shared this morning on Facebook by a middle-school acquaintance who now lives in the great state of Florida,

As ridiculous as that message is, the strategy that it represents is worse. This is how political cleavages become regime cleavages.