In a new working paper, I argue that comparative politics scholarship on democratic backsliding needs to think explicitly about state-society relations. Here is the abstract.

Recent scholarship on democratic backsliding has focused on measuring its global prevalence and identifying the causal processes and mechanisms that produce or inhibit backsliding around the world. But many of the political dynamics that motivate both scholarly and popular concern about the state of democracy are about the desired model of society and the proper role of the state rather than about electoral democracy. This manuscript examines pluralist, populist, corporatist, and integralist models of state-society relations, conceptualizing them with reference to normative models of the modern state and beliefs about the nature of society, and using them to identify distinct varieties of democratic backsliding and axes of conflict within backsliders. Treating conflict over the social ontology of the modern state as “democratic backsliding” obscures a deeper politics of state-society relations, and how those politics independently shape regime contestation in contemporary electoral regimes.

My argument is mainly conceptual, eclectic, and polemical. I want this to be read by scholars and citizens who see the world around us in terms of democratic backsliding, who wonder what it would mean for politics to be actually fascist, who wonder what specifically is populist about Fidesz rule in Hungary or corporatist about Golkar in Indonesia, and who want to organize the cacophony of antiliberal arguments made by actors who support backsliding in the United States and around the world.

I also think that it would do good to move beyond the question of whether or how democratic backsliding takes places, and towards deeper analyses of why and what for. I have been thinking about this quote from Jan-Werner Müller‘s Contesting Democracy:

…seeing the twentieth century simply as an age of irrational extremes or even as an ‘age of hatred’ means failing to understand that ordinary men and women—and not just intellectuals and political leaders—saw many of the ideologies contained in abstruse books (and the institutions that we justified with their help) as real answers to their problems… Many of the institutions…made a further promise to function much better than those of liberalism, which in the eyes of many Europeans seemed like a hopelessly outdated relic of the nineteenth century.

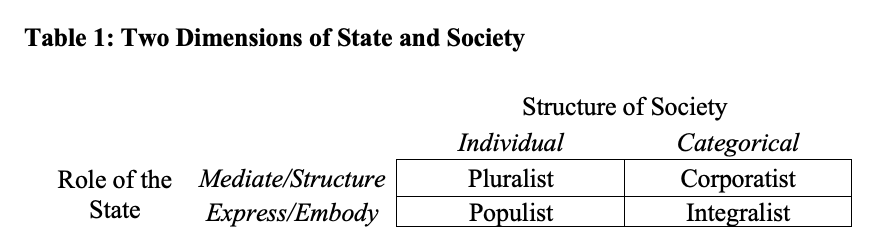

Here is Table 1, the classic comparative politics 2×2 table. (Please read the paper before you get upset about my terminology.)

And here are the conjectures with which I close the essay.*

- Former Soviet and Eastern European countries lived under a form of nondemocratic rule with an explicitly categorical social ontology in the form of Soviet communism in the former USSR and related variants in Eastern Europe. These political orders varied over time and across countries between integralism and corporatism (see e.g. Bunce 1983). Might this history have created a political vocabulary and a societal experience that makes the corporatism of Gladden Pappin (2020) and the integralism of Aleksandr Dugin (2014) particularly resonant within these countries?

- Within modern American conservatism, can we better understand the political alignments that separate Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller, and Elon Musk by focusing on how they imagine the desired the role of the state and their normative model of society (see also Zúquete and Hawley 2024)?

- When conceptualizing Chinese, Saudi, Russian, or any other form of nondemocratic politics, how important is their common absence of competitive elections relative to their distinct models of state-society relations?

- Two what degree is contemporary concern with democratic backsliding actually a defense of pluralism, the model of state-society relations that is most amenable to a liberal, republican, constitutional government?

- To what extent do different types of antiliberal politics—as actually practiced in organizational and partisan form—map onto left-right or second dimension politics?

- What other political alignments (racial identitarianism with social welfarism, technolibertarianism with populism, unionism with clericalism) might be explained by their common social ontologies? To what extent are such alignments anti-democratic by definition?

NOTE

* If you were wondering what could possibly lead me to read Aleksandr Dugin and his political theory of neo-Eurasianism (large PDF), this is why.