A lot of people have a lot of opinions on Gen AI, and I am one of those people.

While AI stans remain breathlessly enthusiastic about large language models and their potential to transform the human species, and haters adopt the Luddites’ position on the social ills associated with not using the computer in the old fashioned way, most people who encounter Gen AI products find them kinda useful for many things.

For example, I like how Gen AI tools like Chat-GPT have replaced StackExchange for helping me to fix up my Beamer presentations and freeing me from the need to remember tidyverse syntax. It also helps to do annoying and tedious tasks quickly, like converting this document (PDF) into a panel dataset just so long as one doesn’t really care too much about accuracy or edge cases.

One area in which I had really hoped to use AI tools to improve my regular workflow is in creating good maps for teaching. AI is know for drawing silly images where people have too many fingers and eyes look creepy, but it has really improved dramatically in recent years and those are now solved problems. Indeed, AI can draw convincing representations of nonsense things like politicians as deities or superheroes, or any other ridiculous prompt that is comprised of reasonable parts.* With this power, surely it can draw useful maps of things that haven’t been represented as maps very often, correct?

I use maps in my Southeast Asian Politics course to represent important things like religion, ethnicity, agriculture, and language groups. One thing I have always wanted to share is a detailed map of where different language families are spoken throughout the region, to highlight at the most general level just how diverse the region is in terms of language (and, therefore, things like human migration and cultural change over millennia). But to do so, I have to use maps of a single language family, like this one from Wikipedia on the Austroasiatic languages (Vietnamese, Khmer, etc):

What I want, instead of this for the language groups within Austroasiatic, is one map that combines six language families, one language per color:

- Austroasiatic (Vietnamese, Khmer, Mon, etc.)

- Austronesian languages (Tagalog, Malay, Batak, Dayak, etc.)

- Kra-Dai (Thai, Lao, Shan, etc.)

- Sino-Tibetan (Burmese, etc.)

- Hmong-Mien (Hmong and related languages)

- Papuan (not a family, but a term for the non-Austronesian languages of eastern Indonesia)

Let us travel, then, on an adventure through Southeast Asia, as cranked through some large language models that are being asked to draw something that probably exists somewhere, but probably not on the internet, and probably not in the exact format that I have asked for. I am not the first person to have noticed some of the challenges described below, but I’m particularly interested in thinking through the implications of a bad map-drawing tool that is easy to use.

Good Enough for Me and Chat-GPT?

Let’s start off with a simple prompt. I am doing all of this below in the Chat-GPT engine called o4-mini-high, which is billed as being particularly good at visual reasoning, but which I had to pay US$20 to use. I am aware that there are other AI engines out there, and you are welcome to explore those if you like. (I will show what happens with o3 below.)

Draw me a map of all of the major language families in Maritime and Mainland Southeast Asia.

Seems simple enough. Here’s what we get.

Oh dear. This isn’t a great start. The computer has used the boundaries of independent states as the boundaries of language regions. The colors in the legend don’t correspond to those in on the map. And the implied groupings are way off. Laos and northern Borneo? Thailand and Myanmar? No Timor-Leste?

But wait, some good news. The text explanation that follows this image is pretty accurate:

Austroasiatic

• Mainland core: Cambodia (Khmer), most of Vietnam (Vietnamese), central and southern Laos, parts of eastern Thailand and Myanmar (Mon).Austronesian

• Maritime heartland: Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia (Malay), coastal southern Vietnam (Cham), plus scattered island groups.Tai-Kadai

• Northern Thailand and Laos (Thai, Lao), parts of southern China’s Yunnan (Zhuang) spilling into Myanmar’s Shan State.Hmong-Mien

• Upland pockets in northern Vietnam and Laos, fringes of southern China.Sino-Tibetan

• Highland fringes along Myanmar–China border, small pockets in northern Laos.Papuan

• Easternmost Indonesia (Papua and West Papua provinces).

This is not too bad. Burmese ought to be also included under the Sino-Tibetan heading, and some languages of Timor-Leste and the Moluccas are also Papuan. Still, call that an A-, pretty good for just being an LLM. (Although fairly disappointing for an intelligence which is supposed to be capable of PhD-level work!) Let’s see if we can fix this up with some prompt engineering.

Can you please label the map with the language families and other information that makes it easier to understand?

In just about a minute, we get our second attempt.

This is definitely worse. There is no city called Hnnooi (and Hainan is not Hanoi). Jakarta is not a language, and it’s not in Malaysia. Papuan is, well, on a different island. Sino-Tibetan is just out there like the Kool-Aid Man declaring which language family claims those waters. And still the colors in the legend don’t match their corresponding polygons on the map, but that’s a second-order concern because they’re wrong.

The text at the bottom of the prompt invites me to keep going:

Let me know if you’d like any further tweaks—such as highlighting subfamilies, showing dialect zones, or adding topographic details!

Why the hell not? Let’s see what this cooks up:

Could you please highlight dialect zones, add the largest mountain ranges and rivers, and make the colors match the regions where language families are spoken rather than the boundaries of sovereign states?

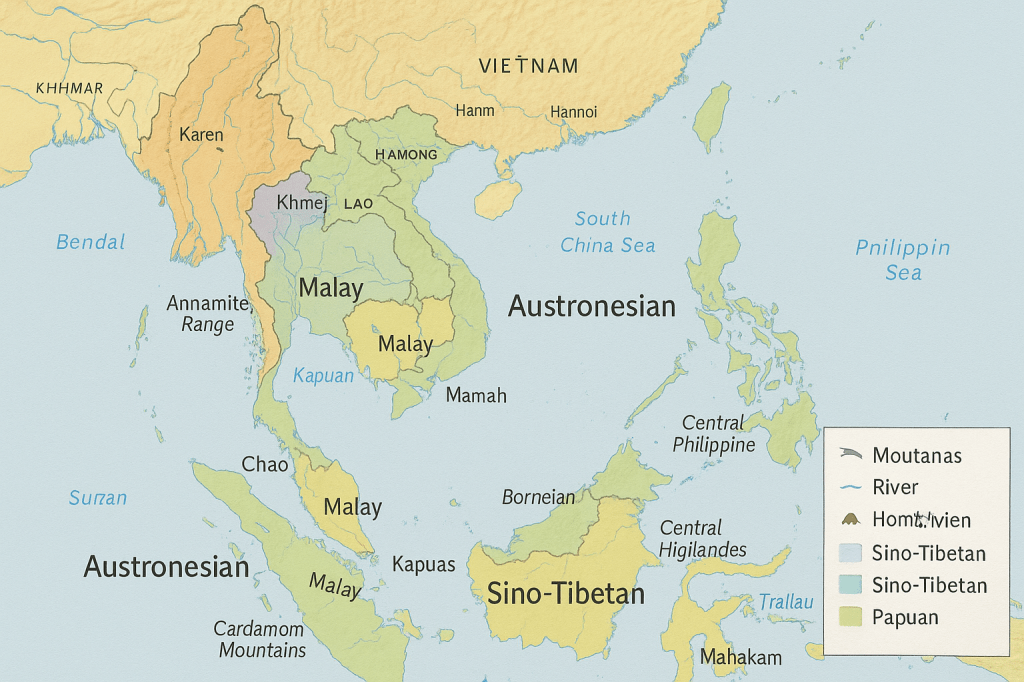

I think I broke it. Where do we even begin? Austronesian has now taken control over the South China Sea. The mountains ranges are off the coasts of the wrong countries. I don’t know what Mamah or Trallau are all about. It used national boundaries even though I told it not to. The legend is bananas. This is bad work.

I tried one more time to get the answer that I want, with more explicit instructions such as the kind that I just provided above.

Can you draw me a map that combines the following six language families, each with its own color, across mainland and maritime Southeast Asia? Colors should correspond to the regions where languages from that family are the dominant language.

Austroasiatic (Vietnamese, Khmer, Mon, etc.)

Austronesian (Tagalog, Malay, Batak, Dayak, etc.)

Kra-Dai (Thai, Lao, Shan, etc.)

Sino-Tibetan (Burmese, etc.)

Hmong-Mien (Hmong and related languages)

Papuan (not a family, but a term for the non-Austronesian languages of eastern Indonesia)

And, well,

Nah you’re way way off, Chat-GPT.

With these disappointing results, maybe it’s time to switch it up. Languages are hard. Religions, though, should be easy, right?

Let’s start over. Can you please draw me a map of the major religions in Maritime and Mainland Southeast Asia?

Bro stop labeling things Hanoi and Jakarta that that are not Hanoi and Jakarta. And also WTF is going on with Australia, eastern Indonesia is wrong, where’s Myanmar, Hindosim/Bangkak, no no no. Actually this map could embarrass someone if they tried to pass it off as literally true. And, the fact of the matter is that if you squint you can kinda see a logic here, so you can imagine someone cooking up this map and not realizing what’s wrong with it.**

If this is disappointing, what about a harder task, something which I have searched for for at least 20 years:

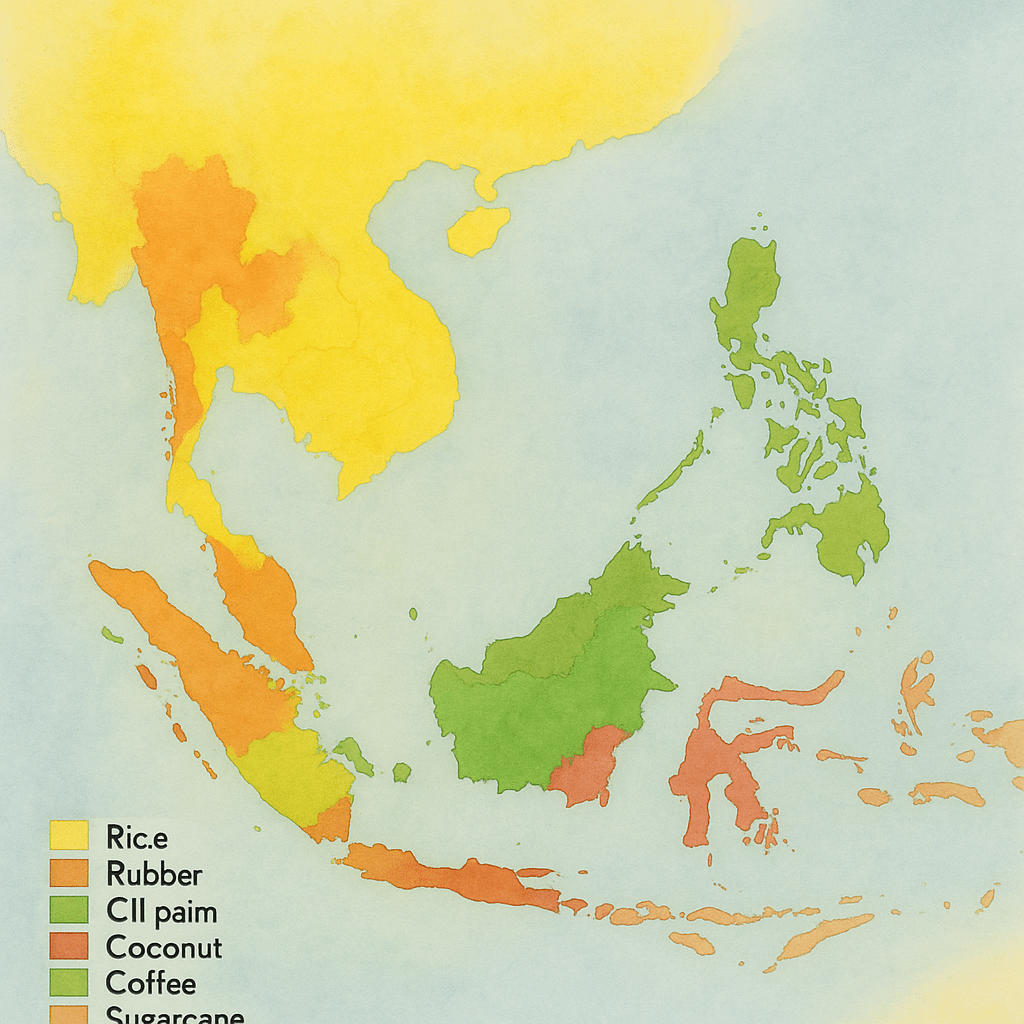

Can you please draw me a map of the major agricultural crops in Southeast Asia? Do not draw country boundaries, just show where different crops are dominant across the region.

I think we’re done here. I’m sorry, Southeast Asia, Chat-GPT cannot map you.

The Poverty of the Stimulus, Gen-AI Edition

What should I make of this? My hunch is that AI-based image tools are particularly likely to struggle when there is a rich base of text from which they can draw, but very little machine-readable information about its orientation in space. To know how to draw the Austroasiatic language family or wet rice goes on a map, you need to know a lot more than a description of where it is. You probably need the raw data already placed on a map with a key to explain what everything means. If that existed already, you wouldn’t need Gen-AI to draw it.***

If the AI was trained only statements like “the Austroasiatic language family is the majority language in Vietnam, Cambodia, and some parts of Myanmar, Malaysia, and India” it simply does not have enough information to generate accurate maps. It needs a lot more detailed information: where exactly in the various countries, where are those locations on a map relative to the rest of the region, on and on. Without that information, it’s like asking a random person what biological order the echidna is in. To answer that, you need to know what an order is, what an echnida is, and how those two things relate. It is an easy question to answer, but only if someone has written that down more or less explicitly.

This reminds me of Chomsky’s argument about the “poverty of the stimulus” and language acquisition among children. Simplifying enormously, the observation is that human language is remarkably complex and generative, so much so that children cannot possibly learn the grammar of any language just by what they hear as children (the “stimulus”). Human intelligence of some form is required to create human language, although it’s not ever described using that terminology in the language acquisition literature.

In this context of being asked to draw a colored map of all the major language families of Southeast Asia, the LLM might just be suffering from the poverty of the stimulus. I have asked Chat-GPT to create sentences (which is all that the instructions to draw a figure are), but it is incapable of answering properly because it doesn’t have a sufficiently rich stimulus—through the text and other data that it has consumed—to allow it to accurately generate those sentences. It’s just the same as if you asked a random stranger to draw this map. AI doesn’t know the answer either, because it, like a random stranger, wasn’t trained on that information.

One might investigate this hunch by trying out a similar challenge where the stimulus is richer; i.e., where there is a lot more text and there are presumably a lot more maps associated with that text. So let’s see what happens if we repeat this exercise in Europe. Easy, familiar, well-defined Europe.

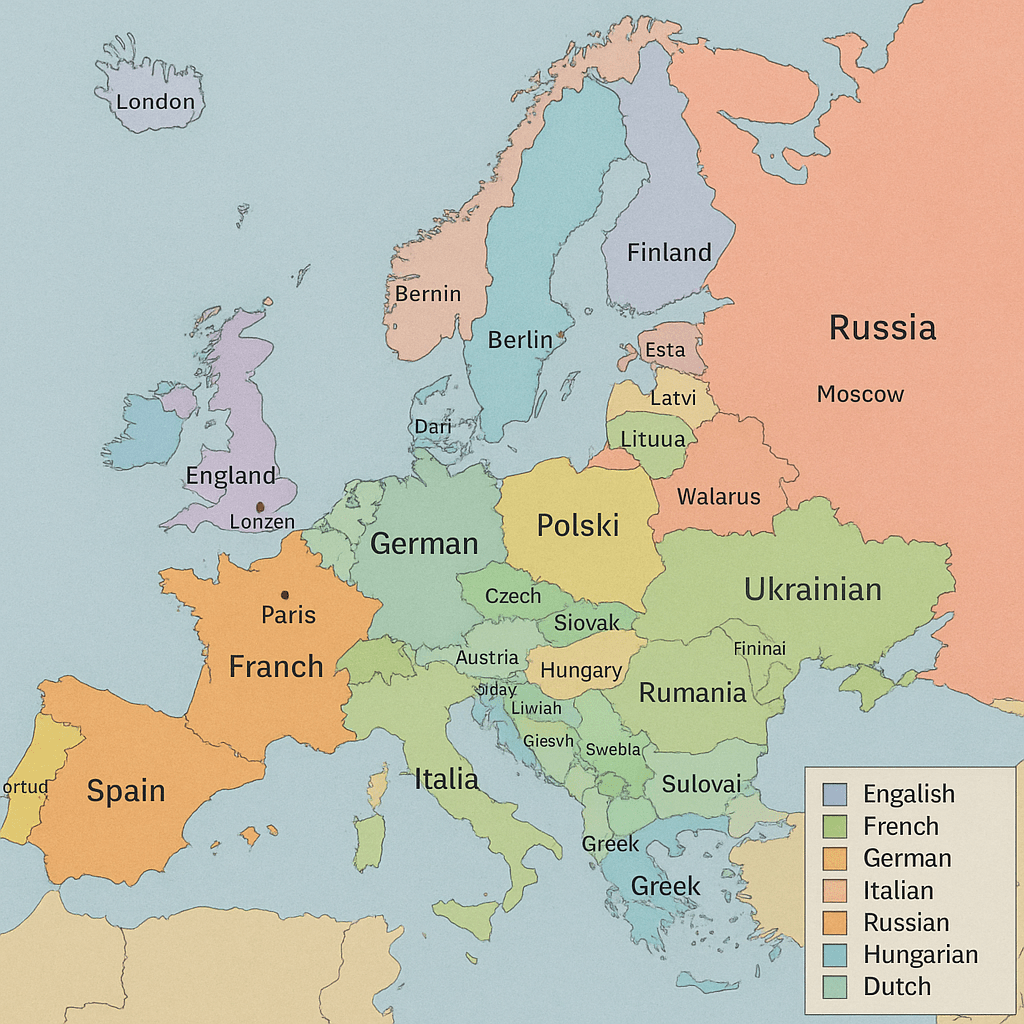

Please draw me a map of Europe in which the colors correspond to the major languages across the continent.

I am sorry to disappoint you, dear reader, but

It nailed Paris! Good job o4-mini-high! But I’m sorry to say it gets, ehm, a little rough as you move to the peripheries. And those colors make no sense. Probably would be a bad idea to let this confident mapmaking machine loose on the Middle East, right?

Please draw me a map of the Middle East in which the colors correspond to the major languages spoken across the region.

This was indeed a mistake and I hope no one gets hurt:

The takeaway point here is that fact-based spatial reasoning is still beyond the reach of the commercially-available AI software. Non-fact-based spatial reasoning works beautifully well (see Ganesha’s bar mitzvah below). Maybe somewhere the engineers are just giving the servers more compute and this will all sort itself out once the costs come down for the super-duper Gen AI engines. In that case, I’ll be delighted because I’ll finally have the map that I want.

It could also be that if I spent a lot more time on the prompts, I could get the AI to generate better results. But that’s not what I need AI for. I could generate a passable version of my Southeast Asia language map in 10 minutes if drawing by hand, in 60 minutes if being very careful using Powerpoint, and probably in about 5 hours using R or ArcGIS if I really needed a polished and reproducible product. There are already GIS tools—some with an AI branding, some without—that take hand-coded geographic information as an input and produce a map as an output.

But for now, I reflect on the gaps between what Gen AI can do well and what it cannot do well, and how that might affect my work as a teacher.

Supervising Chat-GPT: Maps from Data

As I mentioned previously, all of the maps drawn above used the o4-mini-high engine. But OpenAI has others, including o3 which “uses advanced reasoning.” So let finish up this exercise by showing what happens when I work with Chat-GPT to draw maps from actual data.

In the example, my prompts tell Chat-GPT to find actual data and work with that. This creates constraints, because these data might not exist, and if they do, they might be in odd places and oddly formatted. I’ll omit all of the back-and-forth over several hours needed to create these results, but suffice it to say that this first result took about an hour of work and required me to locate and extract .json files while correcting Chat-GPT on several processing/retrieval errors along the way.

This isn’t half bad! It correctly identifies four major language families as well as the locations where they are spoken historically. The empty spots correspond to area where the source data did not include any languages, most notably in highland and coastal Sumatra and in parts of inland and upland mainland Southeast Asia.

Another hour of fiddling with the results (more finding and downloading files, correcting errors, and filling in missing bits with information that I happen to know) leads me to this map.

Now, frankly, this is pretty good. But it’s not close to perfect: some errors include

- Languages in interior Borneo, Buru, and the Sula Islands are coded as Papuan when they should be Austronesian (could be an error in the source data)

- It is still missing the Karenic languages on the Thailand-Myanmar border and the Papuan languages of eastern Timor-Leste, plus some other random languages.

- Tai-Kadai and Hmong-Mien language families should also extend into southern China. The Hmong-Mien region in northern Vietnam is wrong.

- The placement of the languages of Indonesian Papua seems wrong.

- I am not confident about the placement of Hmong-Mien and Austroasiatic languages in Myanmar.

So, at a high level, this is not a bad result. But if you want it to be exactly correct, it is not—and the little errors (like the failure to properly include the Monic languages, for example) could matter quite a bit if you wanted to use this map as a reference.

This result suffices to show, however, that with some supervision and a good deal of domain knowledge and some experience with GIS file structures, you can coach Chat-GPT to create a pretty good map. But if precision is your priority, you still need to do it by hand. And if the goal is to save time and effort, even today’s pay-to-use algorithms might not suffice.

NOTES

* So, if you typed in something like draw me a picture of proud parents Hanuman and Garuda at Ganesha’s bar mitzvah, Studio Ghibli style, you would indeed get a result:

** Yes, I am particularly worried about this coming from the United States Department of State.

*** Unless your goal was just to avoid copyright.